What is the Occoquan Reservoir Watershed and Why Should You Care?

The Occoquan Reservoir supplies about 40% of the clean drinking water for nearly 2 million people who live and work in Northern Virginia and, in an emergency, can supply the whole demand. The Occoquan Reservoir supplies about 40% of the clean drinking water for nearly 2 million people who live and work in Northern Virginia and, in an emergency, can supply the whole demand.

Over half Prince William's total county population, located generally in the eastern portion of the county, depends on the Occoquan Reservoir for about 17 million gallons of clean drinking water each day. West Prince William and Fairfax residents drink a mix of water from the Occoquan Reservoir and the Potomac River, making it difficult to tell where the water is from on any given day.

The Occoquan watershed, or drainage basin, describes the land area where surface and ground waters drain into the Occoquan River. The term 'watershed' describes the land area that drains into a stream, or stream system. The Occoquan watershed, or drainage basin, describes the land area where surface and ground waters drain into the Occoquan River. The term 'watershed' describes the land area that drains into a stream, or stream system.

The Occoquan watershed covers 590 square miles and includes the 1,700-acre Occoquan Reservoir, which serves as the boundary between Fairfax and Prince William counties.

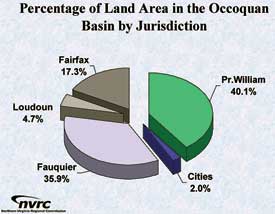

Land uses largely determine water quality conditions. About two-thirds of the land in Prince William drains into the Occoquan River. Water from much of this area enters the Occoquan upstream from the dam: Prince William land accounts for 40.1% of the Occoquan watershed. Land uses largely determine water quality conditions. About two-thirds of the land in Prince William drains into the Occoquan River. Water from much of this area enters the Occoquan upstream from the dam: Prince William land accounts for 40.1% of the Occoquan watershed.

The initial recommendations to safeguard the reservoir included restricting the population within the watershed area to 100,000 people. This was not to be and growth has far surpassed this limitation. According to the 2000 Census, 363,000 people call the Occoquan Reservoir watershed home. Nearly 40% of this population is in Prince William County.

Prince William is an important part of the Occoquan Reservoir watershed. Nearly 40% of Prince William lands drain directly into the Occoquan Reservoir, largely from western Prince William. Impacts from human land uses within Prince William's Occoquan Reservoir Watershed directly affect the water quality conditions of our public drinking water supply.

back to top

What's the Problem?

|

The Occoquan Reservoir is currently listed on Virginia's Dirty Water List. The concerns include high levels of phosphorous, turbidity, low dissolved oxygen, the presence of copper sulfate and the growing presence of pharmaceuticals. These water quality problems are directly linked to human land uses, including a growing population and poor management of development patterns in the Occoquan Watershed.

However, due to variations in data collection protocols between the EPA and Virginia Tech's Occoquan Watershed Monitoring Lab, the Occoquan Reservoir is listed only for aquatic life impairments. Concerns about the presence of copper sulfate, added to Reservoir waters to prevent algae blooms (caused by high phosphorous levels), were discussed but not included in the final 2004 dirty waters list.

Growth and development means that many acres of wetlands and forests are replaced by roads and rooftops. Natural filters are replaced with land surfaces that feed pollutants into the air, water and soil. The land uses in a watershed have considerable impact on water quality. |

Changes to as little as 2% of the watershed area can affect water quality.

|

How Much Stormwater

Does One Inch of Rain Produce?

When it rains, about 5% of the rain water runs off wooded areas and about 95% of the rain water runs off a parking lot. During a one inch rainstorm . . . |

1,360 gallons of water runs off a one-acre wooded area 1,360 gallons of water runs off a one-acre wooded area |

25,800 gallons of water runs off a one-acre parking lot 25,800 gallons of water runs off a one-acre parking lot |

|

The Center for Watershed Protection's groundbreaking research in the 1990's began the trend to quantify human impacts on water quality. Their studies show that watersheds where hardened (impervious) surfaces cover 11 to 25% of land within the drainage area, waterways show clear signs of degradation. Watersheds where impervious surfaces exceed 25% are heavily impacted and typically support no aquatic wildlife.

In 1989, 60% all stream miles in the Occoquan Watershed were classified as high-quality streams. But a 1996 Center for Watershed Protection warned that, given current land use trends, by 2005 only 22% of streams could retain these high-quality conditions and by 2020 over 80% of streams in the watershed would be heavily impacted.

According to the Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC), the most recent detailed accounting of impervious surface cover in Northern Virginia – conducted by NVRC in 2000 – estimates watershed imperviousness to be between 9 and 12% and rising. Many of the Occoquan's subwatersheds are far in excess of 25%.

For many years, Prince William has directed relatively little management attention toward addressing these concerns or the cumulative impact of urbanization on the streams that feed the Occoquan Reservoir. The county is just beginning to consider statistics on impervious surfaces when planning land use and is hopefully moving toward higher standards for managing stormwater runoff. However, even when new policies are adopted, poor understanding about the important links between land use and water quality can prevent these higher standards from being implemented.

Assessments for Prince William watersheds could provide baseline information but are expensive to complete. State and federal funding is available to complement local expenditures, where localities are funding opportunities.

Prince William's 2005 budget again commits virtually no funds to watershed management planning. Local officials might be in a holding pattern, but the costs are growing every day. Contact local officials. |

back to top

Can Conservation Really Make a Difference?

While the recreational values are obvious, Prince William's natural resources also have significant economic value. Stream corridors act as buffers for stormwater runoff and urban pollutants. Forests reduce erosion, protect watersheds and have a substantial stabilizing effect on the world's climate by releasing oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. Wetlands filter pollutants, allow rainwater to filter through to the groundwater supply and prevent flooding. Our air is cleaner. Soil is formed and enriched, nutrients are recycled and crops are pollinated. All this helps keep waterways clean and safe for drinking, swimming and fishing. While the recreational values are obvious, Prince William's natural resources also have significant economic value. Stream corridors act as buffers for stormwater runoff and urban pollutants. Forests reduce erosion, protect watersheds and have a substantial stabilizing effect on the world's climate by releasing oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. Wetlands filter pollutants, allow rainwater to filter through to the groundwater supply and prevent flooding. Our air is cleaner. Soil is formed and enriched, nutrients are recycled and crops are pollinated. All this helps keep waterways clean and safe for drinking, swimming and fishing.

We know that forest and wetland functions are important for good water quality. When these natural buffers are either eliminated or overwhelmed, their functions must be replaced by constructed stormwater systems and filtration facilities. Real dollars are needed to construct alternate systems to replace natural functions.

Although the economics of open space have seldom been translated into dollars and cents, there is growing interest in calculating these values. The numbers are startling at all levels. For example, in 1997 an international team of environmental scientists and economists estimated that the cost benefits received from natural systems worldwide to be $33 trillion (Nature, 1997). The costs to replace nature's services with technology boggles the mind.

Another example comes from New York City, where rapidly degrading watershed conditions threatened the water supply to the point where water quality fell below Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards. Charged with providing over one billion gallons of water every day to New York City and the surrounding communities, officials were faced with hard choices and initiated a review of available options. New York City's analyses focused on two scenarios: technology vs. nature. A study was completed and estimated costs to build a new filtration plant exceeded the costs to restore the watershed area to something close to its original cleansing capacity by a factor of eight. The choice was clear to New York City voters, who strongly supported a bond to begin purchasing forested lands, restoring stream corridors and upgrading septic tanks in the watershed area.

back to top

What's Happening in the Occoquan Reservoir Watershed Today?

The land area that affects the Occoquan Reservoir lies in four jurisdictions: Fairfax, Prince William, Fauquier and Loudoun Counties.

Cooperative efforts and investments from each locality are needed. Some efforts to protect land in the reservoir watershed area have been made by other jurisdictions. One noteworthy contribution came in 1982 when Fairfax County downzoned 41,000 acres of land to protect the Occoquan Reservoir. This also created a buffer area for the Reservoir and an important recreational amenity managed by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority.

Unfortunately Prince William no longer has the option to protect the land area along our side of the reservoir, as Fairfax did in 1982. A variety of residential densities already line this area and the remainder is scheduled for development, including a golf course, with no long-term requirements for water quality monitoring, and residential homes, with septic fields instead of sewer connections.

There are 2060 acres of golf courses in the Occoquan watershed, and 1,080 acres of these are in Prince William County. 52% of total number of golf course acres in the Occoquan watershed are in Prince William County. The county makes up only 40% of the total acres included in the Occoquan watershed. Source: 2000 Occoquan Land Use Survey, Northern Virginia Regional Commission

Many high quality streams still exist in west Prince William. But the area is becoming increasingly pockmarked by a hodgepodge of sprawling low-density residential uses and isolated high-density developments. These uses will eventually overwhelm area streams and increase pollutants that flow to the reservoir.

back to top

What Should Be Done?

Here in Northern Virginia we face two choices: rely totally on technological fixes or begin to incorporate the benefits of natural resource preservation. Development pressures appear overwhelming. We need the schools, offices and homes. We need grocery stores, book stores and restaurants. What can we really do? Here in Northern Virginia we face two choices: rely totally on technological fixes or begin to incorporate the benefits of natural resource preservation. Development pressures appear overwhelming. We need the schools, offices and homes. We need grocery stores, book stores and restaurants. What can we really do?

The first step is to recognize and consider the impacts from poorly managed development. Open space and other natural assets play are integral to good quality of life. We require our buildings to be functional and attractive. We should expect no less for the natural world that supports our built environment.

There is a direct link between land use and water quality. Subtle changes can result in impacts that may seem disproportional at first glance. When even seemingly insignificant percentages of the watershed are converted to roads and rooftops, water quality conditions are impaired.

Stream buffer restoration and land conservation efforts applied to the same area can prevent or offset water quality impairments caused by development. Long-term planning efforts that evaluate development needs from a watershed perspective are a good place to start. Efforts to implement existing rules intended to protect waterways carry no costs and offer significant benefits.

Developers take significantly different approaches in protecting natural resources. Localities that require new development to protect natural resource values help build sustainable communities. New and old developments benefit when communities are attractive and save. There are places where people are proud to live. Developers take significantly different approaches in protecting natural resources. Localities that require new development to protect natural resource values help build sustainable communities. New and old developments benefit when communities are attractive and save. There are places where people are proud to live.

Prince William's proximity to the Occoquan Reservoir means we have an important role to play. As the primary stewards of Prince William's natural resources, we are first in line to receive the benefits. When the balance between human uses and natural systems is upset, Prince William communities will be the first to notice the problems that result . . . and first in line to pay for costs to restore what has been lost.

Thoughtful decisions now would save taxpayer dollars down the road. Conservation of water-sensitive natural features and important natural resource areas is also critical to successful efforts to prevent additional damages. New ideas in conservation design, low impact development and other ways to protect natural resources are developing rapidly. Prince William has many opportunities to protect the Occoquan Reservoir, including establishing and funding a purchase of development rights program.

Currently there is little public participation in the development of public policies in Prince William and little public dialogue. Citizen support for conservation and water quality protection efforts is greatly needed. When all is said and done, choices in the types and amounts of options available to local decision makers is up to local communities.

The first step is to get involved and find out more. The Prince William Conservation Alliance and other organizations host programs on relevant topics. We sponsor a Land Use Roundtable, where citizens, businesses and government share ideas and promote productive activities. Prince William water quality monitoring programs need volunteers. Participation with this program helps you learn how to ‘read' our local streams and helps document current water quality conditions within Prince William.

Only a strong body of active citizens can exercise the political will to change from the current business-as-usual approach. Doing things such as learning more about Prince William, becoming active in our own communities, talking to local representatives, writing letters and participating in public forums can help you make an impact. We look forward to seeing you . . . in the woods watching wildlife, restoring creek banks, sharing ideas with government or participating in local stewardship opportunities. There's lots to do and you can help. Indeed, it can't be done without you.

back to top

More Links

|